Most knitters learn their craft from someone special—perhaps a parent, grandparent, or friend sat you down to explain the basics of that addictive first stitch. Yet knitting has been passed down not just from generation to generation, but from continent to continent, century to century, and there is a rich history just waiting to be

Most knitters learn their craft from someone special—perhaps a parent, grandparent, or friend sat you down to explain the basics of that addictive first stitch. Yet knitting has been passed down not just from generation to generation, but from continent to continent, century to century, and there is a rich history just waiting to be unraveled.

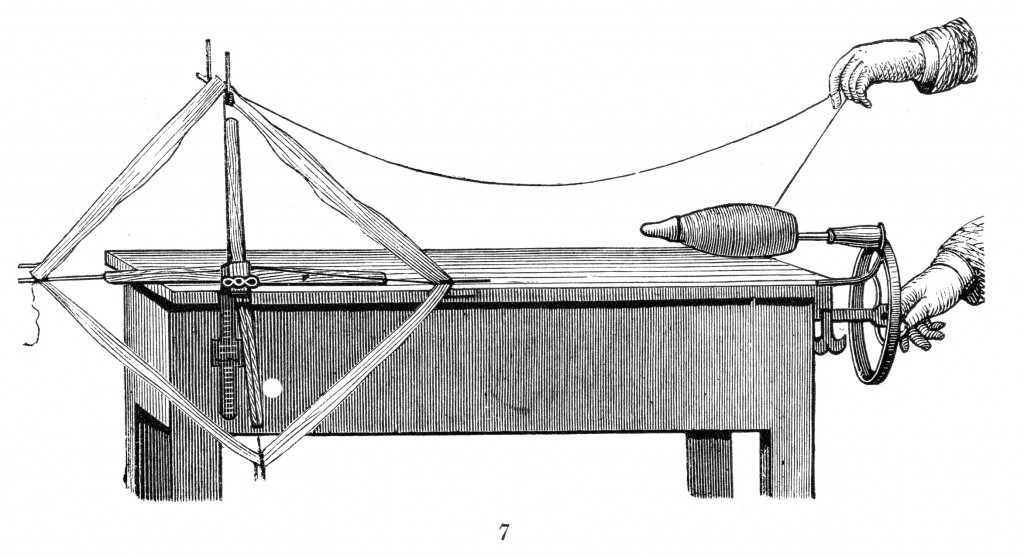

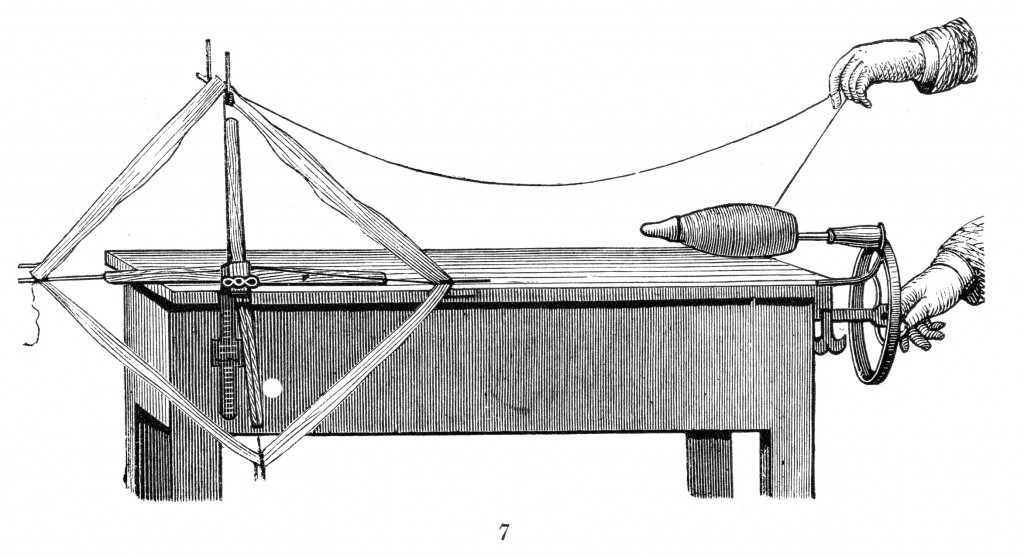

Vintage engraving from 1860 of a Winding machine for a knitting machine

“Needle in a haystack” takes on a whole new meaning when trying to track down that elusive “first” use of knitting. History buffs, knitters, and archaeologists alike struggle to date its invention—and their suggestions don’t just range over a few decades but centuries. For instance, the Society for Creative Anachronism (SCA) writes that it was possible that knitting developed in Islamic countries as early as eighth century while rare pieces, preserved in dry environments like Egyptian burials, are scattered throughout the ninth, tenth, and eleventh centuries. Summarizing Richard Rutt’s well-known book A History of Hand Knitting, the Knitting and Crochet Guild (KCG) offers a very different date: the thirteenth century. According to the KCG, Rutt explains in his book that the earliest piece of knitting that scholars can be certain about are cushions and scraps from Spain and Egypt during this time, although knitting probably evolved out of an earlier technique called nålbinding. Rutt believes that the earliest example of the purl stitch did not surface for another three centuries after that. Davina from the Sheep and Stitch also references early knit socks from Egypt, but dates the time to around 1000 AD. She reminds us of an important point, however: we might never really know how old knitting really is.

“So, if knitting doesn’t have an ancient pedigree, when did it appear on the scene? This is a hard question because many of the earliest knitted garments have disappeared. The reason for this is simple: early knitting was made from natural fibers like cotton, silk and wool – fibers that decompose easily,” Davina writes on her website, the Sheep and Stitch.

Although we may never know exactly which century we have to thank for the joyous match of knitting needle and yarn, the consensus seems to be that knitting originated out of Egypt or its nearby areas. Jessica Pigza, a curator at the New York Public Library, writes that the Mediterranean is known to many as the “cradle of knitting.” We also know that during the later medieval period and the Renaissance, knitting was big, even in Europe. So big, in fact, that just two needles were not enough. The KCG references popular Late Medieval Madonna paintings featured Mary working with up to four needles at a time. Another interesting difference that both SCA and the KCG note is that most early knitting was done “in the round” rather than in back-and-forth rows, a technique which is popular today.

According to Davina, royalty as well as leaders in the Catholic Church were no strangers to knitted attire as early as the 13th Century. As a matter of fact, for much of its history, knitting and status went hand-in-hand, literally—Davina references the elaborate 16th C gloves knit from fine silk and worn by Spanish bishops, which can be seen today in the Victoria and Albert Museum.

In her research, Pigza has found that knitting guilds came into their own in Renaissance Europe. Membership requirements for these guilds were no joking matter: knitters had to spend six years in training before displaying their skills in a final collection, knitted over thirteen weeks, of a hat, stockings or gloves, a shirt, and a carpet.

“Intense as the vetting process was, the guild’s high standard elevated knitting to an art. Certain guilds became well-known for their work,” Davina writes, referencing the six year process for membership.

Useful and, of course, popular, knitting eventually expanded beyond the guilds to the everyday person. And, for those of us who feel we might have once gotten carried away in the name of love, we are no match for the inventor of the first knitting machine, William Lee. According to Britannica, Lee is said to have created the machine in 1589 so that the woman he wanted to marry would focus on him instead of her knitting. Queen Elizabeth I, fearing the effect of the machine on hand-knitters, twice rejected Lee’s request for a patent, so he took his invention to France.

Knitting machines gradually improved over time. According to Knitting History, Jedediah Strutt invented the ribber attachment that made frame knitting possible in 1759, and the following century welcomed the innovation of the circular knitting machine from inventors in Europe as well as America, all perfecting faster and more efficient processes with each addition.

According to Tove Hermanson at Thread for Thought, knitting became a patriotic action in colonial America. As we all know, taxation was the infamous issue, and rebellion was the answer. Americans, particularly women, rejected the high prices of British clothing by turning to the ubiquitous “homespun.” Spinning bees were held to clothe their families and later the revolutionary army, and Hermanson writes that audiences turned out to watch these competitive events, uniting the colonial community.

Knitting, of course, proved important to other war efforts, notably both world wars. Historylink.org elaborates on the value of World War I knitting in its study of areas near Seattle, a microcosm of the national movement for knitted items. As their essay reveals, the home front transformed into a virtual knitting basket. An overwhelming need for warm knitted items came flooding back from Europe, especially the cry for socks to combat the rise of trench foot and the terrible conditions soldiers faced. Thousands upon thousands of wrist warmers, sweaters, and other winter essentials were donated by volunteers, thanks in large part to the advocacy and direction of the Red Cross. Knitters of all ages and backgrounds supported the effort, from children in the Junior Red Cross to college students at the University of Washington to adults. Women fundamentally shaped the war effort, such as Madame Naokichi Matsunaga, who formed the first Japanese women’s organization in Seattle in 1917, members of which met each week to knit. African American women of the Self-Improvement Club in Seattle knitted for African American soldiers and sent their pieces along with other gifts or messages of gratitude and solidarity.

According to the National World War II Museum, just like in the Revolution and World War I, organizations gathered together to provide for their soldiers, working up warm garments and handmade symbols of support. Even Life magazine proclaimed the importance of learning to knit:

“To the great American question ‘What can I do to help the war effort?’ the commonest answer yet found is ‘Knit.’” –Quoted from Life magazine by the World War II Museum

According to Love Knitting blog, US presidents were not immune to the charm or patriotism of knitting. For a few years during his presidency, President Woodrow Wilson kept sheep on the White House lawn to raise wool money for the Red Cross during World War I (though the sheep’s voracious appetite for the fine grass earned them a relocation in 1920). Love Knitting blog also refers to Eleanor Roosevelt as “The First Lady of Knitting” due to her Knit for Defense organization in WWI—and the fierce activist was often joined by her husband.

Today’s era has proved no less fruitful for the craft, hobby, and art that we all enjoy. Knitters donate to charitable organizations, “yarn bomb” (cover with yarn) various structures, or adorn loved ones. When we pick up our needle and fiber, we each participate in a rich history of knitting that has been changing the world for centuries—and is sure to continue to do so.

Thanks you.It was very intéresting.I would know the canadian story of knitting.But the american story is near of our story and we understand our relation by this one…